Solomon Hill

The Coffee King of Liberia

Liberia – Issues 19-27 – Page 54

January 1, 1901

American Colonization Society

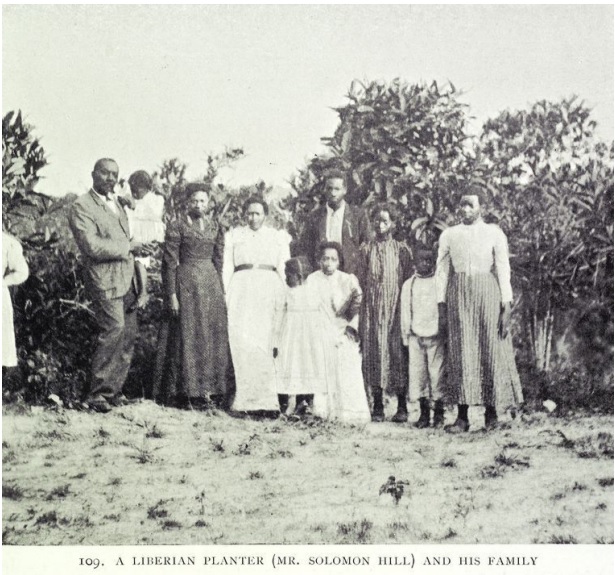

Mr. Myring showed our representative a large number of interesting photographs taken by the party during their journey. photo: courtesy NYPL Mr. Solomon Hill, who is shown in one of these surrounded by his family, is known in Liberia as the Coffee King. Up to the age of twenty-five he was a slave, assessed at the value of $3,000. On being liberated, Mr. Hill reflected that if he were worth that amount to his “boss,” he might become worth as much to himself. Accordingly, he went to Liberia, landing in the country with $3 in his pocket. He is now reputed to be the richest man in Liberia, owning a magnificent house and a steam launch on the river, quite in the approved style of a Mayfair millionaire. — West Africa.

Solomon Hill: wholesome influence on Aborgines

Annual Report of the American Colonization Society, 1888

Letters from Liberia give the following specific information of the efforts of individual settlers. The first refers to Mr. Solomon Hill, of Arthington, who emigrated from South Carolina in 1S71 : — “His influence upon the Aborigines has been most wholesome. Two of the native youth trained by him (Pessehs) are now their own masters and have their coffee farms and live in neat frame houses, cultivating from thirty to fifty acres of land. One of them has recently married a highly esteemed colonist, widow of one of the late prominent settlers.”

Solomon Hill gives 1000 acres of land to native youths

The African Repository, 1891

Mr. Solomon Hill, one of the founders of Arthington, has purchased from the Government of Liberia one thousand acres of land on the road leading to Boporo, on which to settle seven native youths whom he adopted while infants and trained in the ways of civilized life. They have about reached their majority, and Mr. Hill purposes deeding them one hundred acres each, feeling assured that in two or three years they will give a satisfactory account of themselves and their property. These young men received a part of their education in the schools of this Society.

The facts are that the Government of Liberia attracts the social, commercial, and political economy of several millions of Africans, that for leagues about its settlements the kings ‘and chiefs are friendly and even subordinate, and that its people have advanced in civilization and are successfully working out their destiny according to nineteenth century lights.

June Moore, Made a Fortune in Liberia

Liberia Bulletin 9, Nov. 1896, (84-86)

Made a Fortune in Liberia. — So many conflicting statements have been made by returning Afro-Americans and visitors to Liberia, the black republic on the west coast of Africa founded by the American Colonization Society, concerning the climate, people, and resources of that country, and the advantages that the country offers to Afro-Americans as a sufficient balm for all their woes of whatever sort, that it is refreshing to meet a man who went to the country from South Carolina twenty-seven years ago with $5 in his pockets, and who refused to return to this country when friends and relatives did so years ago, and who now has fortune and happiness as the result of his determination to stick, and who can not only visit his friends and relatives in this country, but still have a desire to return to Africa at the expiration of his visit.

The Rev. June Moore, of Arthington, Liberia, is that sort of curiosity. Mr. Moore went to Liberia twenty-seven years ago, in company with several relatives. They all got discouraged and returned to South Carolina. He remained, and is now one of the most considerable merchants and influential citizens of his country. He is a Baptist minister, and in connection with his business interests finds time to do missionary work, having two churches under his charge. He is a coal-black man, of large physique; his features are very regular, and although he must be over 50 years of age, he has no gray hairs in his head, and his teeth are well preserved and perfectly white. He has been in the country some weeks, visiting his relatives in South Carolina and attending to business in New York and Philadelphia. He will leave for West Africa by way of Liverpool, on Saturday of this week. ” Is it as warm in Liberia as it is in New York?” asked The Sun reporter, as he mopped the perspiration from his face.

” No, sir,” said Mr. Moore ; “we seldom have it as warm as it is today here. Our heat is regular, not spasmodic like yours, and our mornings and evenings are invariably cool and pleasant. I find that the Liberian climate has been much misrepresented over here.” ” How about that terrible Liberian fever ? ” Mr. Moore’s face clouded. ‘ ‘ Don’t you have plenty of fever in the sea islands of South Carolina and in the Mississippi valley, and in all of the West Indian islands, and is it not malignant ? There is plenty of fever in all tropic and semi-tropic countries, and if we do not observe proper caution it will kill us. We have fever in Liberia, but it is only dangerous to those who don’t observe proper caution in their clothing, diet, and exposure to the sun.”

” What are the staple products of Liberia? “

” Coffee, ginger, and food products. Coffee is the most profitable, and everybody goes in for coffee culture. It takes five years for a coffee plant to mature. We raise some sugar, and could raise more if coffee culture was not more profitable. Yes ; we can raise cotton, but we do not do much of it, because it does not pay as well as coffee. We raise plenty of hogs and fowls. Horses do not thrive very well, but we find that the donkey does well, and he is being gradually introduced. Mules? We have not tried them, but I should think they would do well. Oh, yes ; we have coal, but it can’t be worked profitably until we have a railroad from the interior to the coast. A railroad concession has been granted to an American. Our people are much interested in the construction of it.”

“What is the population of Liberia?”

“We have about 22,000 of the American stock and a vast native population. We are gradually changing our policy towards the natives, paying more attention to them, and we hope eventually to have a large and strong citizenship from that source. The supply from which to draw is well nigh inexhaustible. The early policy was to leave the native population to shift for itself. To my mind this was a fatal error, and our people are, beginning to look at the matter that way. Oh, yes; the natives make good citizens when properly educated.”

” What sort of education do the natives need ? ”

” Industrial education,” said Mr. Moore. “Then, of course, we need educated native missionaries. They should be educated right in Africa. When educated abroad they get too far out of touch with their people, and too often have no disposition to return to the work for which they were educated. You can’t christianize these people all in a hurry ; you have to allow somewhat for their heathen religion and customs. Take a man with six wives, for instance. His religion allows it, ours condemns it. The man may want to become a Christian, but he may not be willing to give up all his wives at once. We have to bear with him, wrestle with him, until the force of the Gospel makes him see the error of his ways. So it is in many other practices which are a part of the religion of the people.”

“What do you think of Afro-Americans going to Liberia to better their condition?”

Mr. Moore scratched his head, which showed that one peculiarity of the South Carolina Negro in perplexity had remained with him after a residence of twenty-seven years in Africa. ” I think that it is a pure question of manhood,” said Mr. Moore ; ” a pure matter of self-reliance. I am always afraid when I see a large number of American Negroes come to Liberia on this account. They do not have sufficient self-reliance to work out their salvation, and soon grow discontented because of this and because they do not find things in Liberia as had been represented to them. Removed from contact with white men, up to whom they had always looked for advice and direction, they soon want to return to the United States, and when they do, they bring bad reports of the country. They did not prosper in Africa because they could not stand alone, and they do not prosper in this country for the same reason. People have to work hard and save something of what they make, and have patience in Africa as well as in America. My brother and several others who went to Africa with me twenty-seven years ago soon got tired and restless and returned to the United States. They also wanted me to do so, but I declined. I felt that I was better off in my freedom and could save more in the end in Africa than in America. I pulled off my coat and went to work, and kept working until fifteen years ago, when I succeeded so well that all I had to do was to superintend my business. Today I am prosperous and happy. My relatives and others who returned to South Carolina are worse off in this world’s goods, in their freedom, and in peace of mind than they were twenty-seven years ago. They would be independent and happy men today if they had remained in Africa and had had the manhood and courage to labor and to wait.”

“Then you think that what the Afro-American Negro needs is more reliance upon himself and less dependence upon white men ?”

“Decidedly,” said Mr. Moore. “There is the cause of most of their troubles. They expect white people to do for them what they should do for themselves. That is the way they were educated in slavery. I found in South Carolina that the whites now have all they can do to look out for themselves ; they have no time nor inclination to care for the blacks, who are as free as the whites, and are expected to depend upon themselves as free men should. Teach the American Negroes self-dependence and reliance and they can get along anywhere ; without these elements of manhood they will fail anywhere.” — T. Thomas Fortune, in “New York San.”

The Bright Side of African Life – Page 30

Jan 1, 1898, AME Publishing House

The name of Hill and Moore is a synonym for all that is progressive in Arthington and in Liberia. Mr. Wallace F. Moore, the leading, business man in the firm, was born in South Carolina, York County, in 1868. His parents, Rev. June Moore and Adeline Moore, immigrated to Liberia in 1871, bringing Samuel, James and Wallace. Rev. June Moore is a Baptist preacher and believed that God desired him to return to his fatherland to educate and rear his children.

Wallace F. Moore was taught by his father at an early age — yet he did not have a large stock to put out to his son — but Wallace was sent to school to E. S. Morris and then to Rev. R. R. Richardson, D. D. But his eyes failing, he was sent to the United States for treatment. On returning, he was placed at Rick’s Institute, the leading Baptist school in Liberia. During all this time the Moores were very poor and could not afford to have a large boy at school all the while, so Wallace went at intervals. Like his father, however, he had ability, and an opportunity was all he needed. In 1890, he entered the store at Monrovia, and thus finished his education in the practical school of business. He married Miss Hoggard in 1890, and is the happy father of two children and husband of an affectionate wife. He is a leading member of the Baptist church. He is superintendent of the Sabbath school. He is also secretary of the Baptist Association, corresponding secretary and financial agent of the Baptist churches of the Association. The firm of Hill and Moore, of which Wallace F. Moore is the leading business man, does more than one hundred thousand dollars worth of business annually. Prof O. F Cook is a white man from New York, or Boston. He is president of the Liberia College and agent for the Colonization Society; he has a large farm in this settlement at Mount Coffee. I am told domestic slavery exists here, as it does on many farms owned and controlled by Afro Americans who were once slaves themselves, and that inhumanity plays its part with whip and driver. Prof. Cook came to Liberia with the idea that the white man must rule under any and all circumstances, and that his agency for the Col onization Society and presidency of the’ Liberia College made him President of Liberia and manager of the United States Legation. Prof Cook is a learned man. He spends about three months in Liberia looking a ter the college and farm. The other nine months the overseer controls the farm and slaves while the college is man aged by a single professor. The Colonization Society has missed its high and holy calling, and is now the seeker afier gold and the enricher of an individual who has no interest in Liberia, only as it affords him comfort and puts dollars into his pocket. Even the color line, I am told, has been tightly drawn by this learned professor.

The African Repository – Volume 48 – Page 351 – Google Books Result

The African Repository – Volume 49 – Page 339

https://books.google.com/books?id=9J0kBtW-qhEC&pg=PA339&dq=june+moore +liberia&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjbj77txsHNAhVBSyYKHVg7CwcQ6AEIUTAJ#v=o nepage&q=june%20moore%20liberia&f=false

Liberia: the America-African Republic: Being Some Impressions of the …

Arthington

I passed over hills and through dales. It is a charming country. I imagine myself there now. It can not be described, at least I am not equal to the task. Coffee and sugar farms are on every side, some stretching far and wide. The majestic cotton-tree towers high, and looks smilingly down upon the graceful palm. The shrubbery, owers, and grass are attractive to the eye, presenting every variety of color and form. The beautiful birds sing amidst the leaves, or it across my path as if to show their gay colored dress. Standing upon one of the highest hills, looking over the country, listening to the roar of the St. Paul’s dashing over the cataracts that impede navigation, I have wondered where in all God’s universe could one see a more beautiful sight. As I look away into the distance, I see houses scattered here and there. It is Arthington, bosomed in the green hills alone! There is nothing about the place to describe. It is a settlement rather than a toWn. Its people are healthy, industrious, prosperous, and happy. It is the leading settlement in Liberia. Fifteen years ago the place was a wilderness. Mr. Robert Arthington, the wealthy manufacturer of Leeds, England, wrote to the American Colonization Society, oflering to donate one thousand pounds sterling, or ve thousand dollars, toward sustaining a settlement in the interior of Liberia which would be the beginning of a line of settlements to extend across the continent, connecting the East with the West Coast, Abyssinia with Liberia. The place-named after the distinguished philanthropist resulted from this offer. A colony of emigrants from North and South Carolina headed by June Moore and Sol Hill, of Union County, South Carolina, plunged into what was then a primeval forest, slept on the bare ground, while their wives aided them in the work of cleaning the land and building homes.

I have listened with astonishment to their thrilling story. How the men’s hearts failed them when they found themselves set down in a barren wilderness! The women—and they told me themselves—felt home-long ings for a moment. But a heart-wrench, and they were gone; and like heroines, they settled down to do or die! They inspired their husbands with superhuman power. They bravely shared the inconveniences, hardships, sufferings, and perils of the wilderness. But now sitting in their comfortable homes, many said to me with honest enthusiasm and pride, “I would not return to live in America if I could.” They live in neat, comfortable houses. They have prosperous churches; there is an excellent school supported by Edward S. Morris, of Philadelphia ; there are thousands of acres of land under cultivation ; and they are pushing further into the interior. In December, 1883, the young men of the settlement held a meeting and resolved to form a colony and.push further back towards the interior. Brave young men. In other parts of Liberia, they seem to be content to clerk for a pittance, to get into the Government service, or to loaf “ until the old man dies.” Then they move into the paternal home, and live on the accumulations of the fathers, and let things run down l Arthington is a model place. An election was pending. A candidate, I was told, sent up to the settlement goods for distribution, hoping in that way to Secure votes. The bribe was returned, and, the vote of the settlement was solid against that man ! If one could see the energy and industry so characteristic of the people of Arthington more general in the Republic, he would become an ‘enthusiastic colonizationist. This thriving settlement shows that carefully picked pioneers in interior settlements can direct and control and utilize the native material, and through it develop the country. The conditions for the future prosperity of Liberia are found in Arthington. Its people seek Christian education, follow industrial pursuits, and fuse with the natives.

African Repository

VISIT TO ARTHINGTON.

BY PROF. EDWARD W. BLYDEN.

I have just returned from a visit to Arthington. This settlement, about thirty miles inland from the sea, was founded in 1869 by as noble a set of men as ever returned to this country from the house of bondage in America. They were chiefly from the Carolinas. They came without money or book learning — their only capital being the mechanical and agricultural knowledge and experience and the habits of industry which they had acquired under their taskmasters. But they had something else also, even more important than the qualities just described, viz — they were thoroughly identified with the Negro race. They were born with faith, hope and love for Africa. Some knew the tribes to which, by unbroken connection, they were related, and came prepared to labor and suffer to build up with pride the waste places of their ancestral land and to lie down beneath the sod when their labors were over, with joy and satisfaction, mingling their dust

with that of their forefathers.

When they arrived they had to confront an impenetrable forest, six miles from any settlement. Their women were left for shelter in the settlements, while they went out to contend with the unbroken wilderness, make clearings and build their huts, eating the fare which, after dividing with their families, was left to them from the Society’s rations.

I visited the site of this settlement in 1869, on my way to the interior, and the only sounds then heard were those made by the birds on the tops of the lofty trees.

There was no opening through the thick forest and dense undergrowth but the narrow path traveled for generations by the natives. 1 visited it again in 1873, when the settlers had made astonishing, progress. The pioneers were all living, rejoicing in their recent and increasing triumphs over the wilderness, and full of confidence and hope, determined to carry their conquests further eastward. The solitary place had been made glad for them and the wilderness was blossoming as the rose. (See Repository, Dec., 1873.)

I visited the settlement again in 1877, on my way from Boporo (see Repository, Nov., 1877), and they had made such inroads into the forest as astonished me. They were then beginning to attract to their neighborhood and under their influence the untutored denizens of the aboriginal districts.

My visit a few days ago, after eleven years, only served to heighten my respect and admiration for the energy, industry and patriotism of the settlers. They have enlarged their borders in every direction. They have built commodious and substantial frame houses and extended their coffee farms along three avenues, skillfully laid out. Two of the avenues run from east to west, generally parallel with the St. Paul’s river in the direction ot Clay- Ashland. These are called Bertie and Georgia avenues. The other avenue at right angles with the two just mentioned is the chief thoroughfare and runs from the St. Paul’s to the interior. It is called South Carolina avenue. It is very likely to be continued right through your next interior settlement, eight miles beyond, which, it is hoped, will soon be established.

Rev. June Moore, a Baptist preacher, and Solomon Hill, both immigrants by the “Edith Rose” in 1871, are the leading men of the settlement. Mr. Hill is probably the most independent man, as a man, in Liberia or the whole of West Africa. He is literally the architect of his own fortune. He is carpenter, cabinet maker, blacksmith, engineer, farmer. When he landed in Liberia he was the owner of only thirty dollars, and when the hut for his first residence was finished he had not one cent left, with a dense forest all around to be overcome. With trust in Gotland a splendid physique, he went to work, cleared and planted, doing all the work himself. He has now a large two story frame building with verandah and attic, and outhouses for his hands and produce — some covered (roof and sides) with corrugated iron. He has planted one hundred and eighty acres of his land with coffee alone ; in other portions he has breadstuffs and other things growing.

He built his house himself and made his own furniture. His bedsteads and tables are specimens of first-rate workmanship, and being made of native wood procured on his land, is far superior to anything of the kind he could import. His skill would command patronage in any city in the world. As a blacksmith he makes his own tools. His lathe for turning wood and iron was constructed by himself in a very simple but effective style. Beginning with no money capital, he is now, a greater producer of coffee than the Muhlenburg Mission in the neighborhood, begun more than ten years before the settlement, and has enjoyed large pecuniary advantages. Mr. Hill has in store fifty bags of coffee from last season, which he has been under no necessity to sell. It is now thoroughly cured and will command a high price. He will produce ten thousand pounds of coffee this season, besides other agricultural articles.

His influence upon the Aborigines has been most wholesome. Twoot the native youth trained by him (Pessehs) are now their own masters, and have their coffee farms and live in neat frame houses, cultivating from thirty to fifty acres of land. One of them has recently married a highly esteemed colonist, widow of one of the late prominent settlers. Mr. Hill is still in the prime of life and is constantly enlarging the sphere of his labors and influence towards the interior. He claims to be, on his mother’s side, of the Golah tribe, one of the indigenous tribes of Liberia, and on his father’s side from one of the tribes on the Niger. I have dwelt so long on Mr. Hill’s case not because he is exceptional in energy, industry and patriotism, but because, taking him all in all, he is the most remarkable of the Arthingtonians. He can neither read nor write, but he is a man of power.

The other settlers are all of the same spirit, temper and enterprise. The majority can barely read, and only one of them knows anything of grammar, and that is a grandson of the late Alonzo Hoggard, the leader of the first settlers. This exception is a young man who spent three years in Liberia College (1881-84), and is at present teacher of the Colonization Society’s school in the settlement.

The children born in this settlement are physically stronger than those born on the coast, and their parents compel them to labor. Every youth, from 16 to 20, has his coffee farm under the supervision of his parents. Thus trained and in cooperation with the natives they will perpetuate the labors and methods of their fathers. Arthington must live, for it takes the Aborigines along with it in all its religious, social and industrial movements.

Now what becomes of the theories of those who tell you that the character of the emigrants you are sending to Africa is not such as to benefit the country — that they are ignorant, illiterate, &c. The fact really is, that the emigrants you have been sending us for the last ten or twenty years, or since the civil war, have made a greater impression upon the country in the direction of productiveness and material independence than all those sent before the war, who, as a rule, adhered to the coast, engaged in a precarious trade, or relied on missionary or government employment. Visitors to Liberia, who see only the coast settlements, can get no idea of the actual condition or possibilities of the country— the impression of such persons would be rather unfavorable to the country than otherwise. (See Bishop Haven’s letter in Repository, Oct., 1877.)

June Moore gave me an interesting and suggestive account of his difficulties in 1870 when, desiring to emigrate to Africa, he sought information about Liberia. He wrote to different prominent officials in his State, but not one knew anything about Liberia or could give him any clue to the subject. At length he wrote to the Collector of Customs at Charleston, who referred him to Dr. John B. Adger, Professor at Columbia, S. C. Dr. Adger replied that there was such a place as Liberia, but it was a failure, the colonists being lazy and unenterprising, but that if he wanted further information he should apply to the Secretary of the American Colonization Society at Washington. He did so, and was, in a few days after, placed in possession of copies of the Repository and other documents referring to Liberia. From that day to this he has read the Repository with the greatest interest, and has never been deceived by its pages. He has found Liberia for the Negro who loves his race and Fatherland, and who will work, the best country under the sun. But there are thousands of Negroes, perhaps millions, in the United States who know nothing of Africa ; and, as a rule, if they make inquiries, Liberia is described to them as Dr. Adger described it.

On Saturday evening, Nov. 10th, I lectured in the Baptist church of the settlement, which holds about 250 persons, to a full house, on the origin of Arthington, the work thus far ‘accomplished and the prospects before them. I told them that their settlement had its origin on Mount Lebanon in Syria, July 26, 1866, the anniversary of Liberia’s independence, when the American missionaries there, desiring to celebrate the day, requested me to address them on Liberia.

After the address (see Repository Oct., 1866) which appeared in the Repository Dec., 1866, and afterwards in pamphiet form, Dr. H. H. Jessup asked me if I knew Mr. Robert Arthington of Leeds, England. I said I did not. He then described that philanthropist and his generous deeds, and advised me to write to him about the young Republic. I did so then and there, and out of the correspondence thus initiated grew the settlement of Arthington. Many present had not heard before of how their settlement had come to be, and were glad to know that the idea of its foundation was conceived in the land of the apostles and prophets. Next morning, after the lecture, June Moore’s eldest son reminded him that he was born on the very day of my address on Mount Lebanon, July 26. 1866, a coincidence which deeply impressed the young man.

Sunday afternoon, Nov. 10th, I addressed the Sunday school of the Baptist church, a large number of adults attending. In the evening I lectured on “The Negro’s Heritage in Africa,” describing the countries’ interior of Liberia and Sierra Leone, which I had visited, their population, industries, customs, &c., of both Mohammedans and pagans. At the close of the lecture Mr. June Moore, who presided, in returning thanks to the lecturer, said he had read my recently published book and other writings of mine, but had not fully understood them until that evening— that the lecture was the key to my published writings.

There is in this settlement a flourishing Woman’s Missionary Aid Society connected with the Baptist church. Its President, Mrs. Mary Ann Kershaw, having recently died, the Sunday morning service was devoted to commemorating her memory. Rev. June Moore, pastor of the church, delivered a most interesting address from Hebrew iv, 9. Fifteen of the members of the Society, dressed in pure white, with hats covered and trimmed with white, took their seats on the left of the pulpit. The preacher, in his reminiscences of the deceased, depicted a most suggestive and forceful character— a Negro woman of constructive and executive ability, possessing all the qualities suited to impassioned eulogy, admirably

fitted to be the wife of a pioneer. In her death, as in her life, the preacher said, she was triumphant. Her husband, advanced in years, and their sole surviving daughter, sat there, and smiling through their tears, as the sayings and doings of the great woman were discussed. The congregation was requested to sing two of her favorite hymns, viz. : “Prayer is the soul’s sincere desire,” and “On Jordan’s stormy banks I stand.”

One acquainted with the history of this settlement could not but feel, as he surveyed the whole scene, “What hath God wrought !” The preacher informed me after the service that he received most of his training in Liberia. He knew nothing of religion in America. He belonged to a Presbyterian family, but he had no religious impressions till he came to Africa. Here he became converted, joined the Baptist church, entered the ministry, and has recently been elected pastor of the church. He informed me that the church having grown too small for the membership, many of whom are from the neighboring tribes, they intend soon to erect a much larger building.

Returning from Arthington, I spent a night and part of a day at the Muhlenberg Mission, which is a continuation of the industrial energy at Arthington . Indeed, this mission in the early days of the settlement was a great support to it.

I found Mr. Day, the energetic superintendent, in his usual health and abounding activity. I visited his large workshop, under the superintendence of Mr. Clement Irons, a pure Negro, who emigrated in 1878 from Charleston, S. C., in the “Azor.’ ’

The boys of the mission are trained here in various handicrafts. They build carts and wheelbarrows, run steam engines, make farming implements, &c. Mr. Irons has constructed a steamboat for the river of native timber. It was launched from the mission a few weeks ago by the pupils only — 75 of them took hold of it and pushed it from the mission hill down into the water. This mission seems to me to be a model for missions in this country.